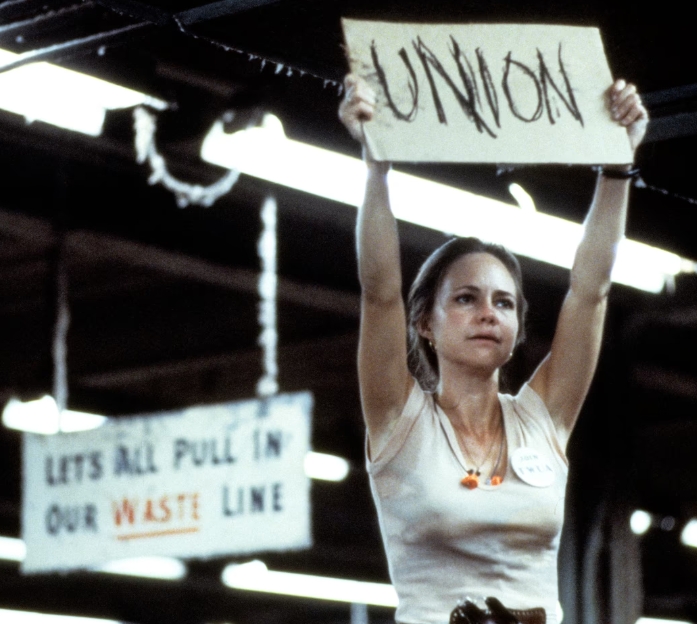

Sally stood on a set carved from dust, machinery, and real-life tension—the trembling weaving looms of a Southern textile mill. It was a sweltering Alabama August in 1979, and sweat pooled in the creases of her uniform. Every hum and throb of the factory felt alive, urgent. She breathed it in, let it sink into the soles of her feet. Here was Norma Rae—the defiant soul determined to stand tall, even when everything around her shook.

But Sally wasn’t just playing Norma Rae. She was wrestling her own fate.

Hollywood only remembered her as Gidget and The Flying Nun—light-hearted, quirky, distant from dramatic heft. No one took her seriously. She wanted to claw her way out of that persona. The role of Norma Rae Webster was her crucible, her chance to rediscover the core of her talent, and her voice.

She trained relentlessly, not in dance or lines, but in rhythm. She mimicked the coughs and weariness of mill workers. Two hours in that weaving room felt like eight somewhere else—“the room shook, you’d go seasick,” she later recalled. Her muscles ached. Every swing of her foot on that table at the union rally echoed in her bones.

Behind the cameras, her heart was battered too.

Her then-boyfriend, Burt Reynolds—smoldering movie star, public heartthrob—dismissed her ambition. “No lady of mine is gonna play a whore,” he sneered when she told him she’d accepted the role. She tried to explain the character’s dignity, her grit, but he mocked her, saying, “Now you’re an actor…”

She bristled inside. This wasn’t a lover’s protectiveness. It was a cage.

When the screenplay required her to stand on a table, voice raised in defiance, Sally didn’t hesitate. On filming’s final day, a wedding-ring awaited her—not celebration, but confinement. Burt popped the question. She said only, “Thank you,” then walked away. That moment felt like stepping free—and terrifying. She wasn’t sure who she was without complacency.

The set was real: mill workers, 14-year-olds to 50-year veterans, all alive with fatigue and longing. Sally absorbed them. She saw pride clash with despair in their faces. She learned from the men and women who fought despite exhaustion that dignity doesn’t wait for permission. She carried that lesson to every rehearsal.

At Cannes, standing on that stage, she held her breath as a film critic announced her name for Best Actress. Tears spilled sideways. Critics had taken notice. She felt the weight of every silent naysayer fall away.

But back home, Burt wasn’t supportive. He refused to attend the Oscars with her—even at Cannes. On The View, Ana Navarro later described it as ego—her rising did not comfort him. He questioned: “You don’t think you’re going to win anything, do you?” he had said.

But when the Oscar envelope said “Sally Field,” her smile was like sunlight. The role had delivered her truth, and she carried it forward.

Years later, during press for Lincoln, she revisited that fire with new clarity. Method acting—something she’d always practiced quietly—flourished under Steven Spielberg’s thoughtful direction. She cried when previews showed the emotional terrain she’d built. She treasured the studio created for her as Mary Todd Lincoln where she could fall apart and rebuild without guilt. The confidence she’d forged as Norma Rae carried her through.

But in the winter of her memory, she spoke of the relationship she’d needed to leave. In her memoir In Pieces, Sally wrote of Burt’s jealousy, control, and possessiveness. She acknowledged how the role—and her growth—would have been stifled under those constraints.

Now, looking back, she saw that the break confirmed everything: she wasn’t just beating stereotypes onscreen—she was breaking them off camera too.

In the quiet of her home, Sally sometimes sits with her Oscar. Not to rest on it, but as a burning symbol: a lampshade for stories untold, freedom earned, the unknown battle scars that shaped her.

Her characters—Norma Rae, Mary Todd Lincoln, and more—carry fragments of that fierce moment when she dared stand tall.

She taught herself that anger has shape, courage has voice, and sometimes, searching for dignity is its own union.