The apartment was quiet, save for the soft hum of an oxygen concentrator in the corner and the rhythmic ticking of the antique clock on the wall — a gift from a fan decades ago. Michael sat in his favorite armchair, sunlight catching the silver in his hair, the tremor in his left hand subtle but constant.

He wasn’t filming anything. There was no set, no lighting crew, no script. Just him, a cup of tea growing cold, and a journalist named Dana who had been granted rare access—not for a promotional interview, but for something far more personal.

“I don’t want this to be a legacy piece,” he said, looking her straight in the eyes. “I’m not done yet.”Dana smiled gently. “Of course not.”

Michael chuckled dryly. “Though I have to admit, some days I feel like I’ve lived ten lifetimes.”

There was weight behind the joke—thirty-plus years living with Parkinson’s disease had carved stories into every movement he made. What was once barely a tremor had grown into something louder, more persistent, like a storm tapping insistently at the windows of his body.

“It’s banging on the door now,” he said softly, echoing words he’d spoken in another interview. “And I know it’ll get in eventually. But I’m not opening it just yet.”

Dana nodded, her recorder running, but forgotten. “What keeps you going?”

He glanced toward the bookshelf, filled with photos of his kids, his wife Tracy, and old scripts from Family Ties and Back to the Future. A life cataloged not just in film, but in love.

“This,” he said, gesturing with a stiff arm. “This whole room. Every moment I’ve gotten to live. Every fall, every fracture… they hurt, sure. But they remind me I’m still here.”

He paused.

“There was a time when I broke my cheekbone in a fall. Then my hand. Then my shoulder. Three months later, my arm. I was starting to feel like a bad stuntman in slow motion,” he said, laughing at his own grim joke. “But I kept getting up. Not out of bravery, but because I didn’t know what else to do.”

Dana was quiet for a moment. “You once said, ‘You don’t die from Parkinson’s. You die with it.’ Do you still believe that?”

Michael’s face shifted—something between a smile and sorrow.

“I do,” he said. “But you have to understand what that means. It’s not about defying the disease. It’s about living beside it. Letting it ride shotgun while you try to steer.”

He looked down at his hands, fingers twitching slightly. “People think I’ve been fighting Parkinson’s. I haven’t. You don’t fight something that’s part of you. You dance with it. Some days you lead. Some days, it does.”

Dana leaned forward. “And what about the future? You once said you don’t think you’ll see 80.”

He exhaled slowly. “I said that. And maybe it’s true. But I’ve already lived longer than I ever expected to when I was first diagnosed.”

He shifted in his chair, struggling a bit before settling again. “We live in this culture that’s obsessed with winning. Winning the battle against cancer, against age, against anything that dares slow us down. But not all victories are loud. Some are quiet. Some are just… waking up and choosing to smile.”

There was a silence that followed—thick and reverent.

Then Michael added, “I don’t need 80 years. I just need today to matter.”

Later, as Dana was preparing to leave, Michael insisted on walking her to the door. It took time. He moved cautiously, with the cane he had once resisted using, steadying himself with quiet dignity. Each step was deliberate, as if the floor beneath him might shift at any moment—but he kept moving.

As they reached the door, Dana turned to him.

“Thank you. For your honesty. Your openness.”

He nodded. “Thanks for listening. It’s nice to be seen beyond the disease sometimes.”

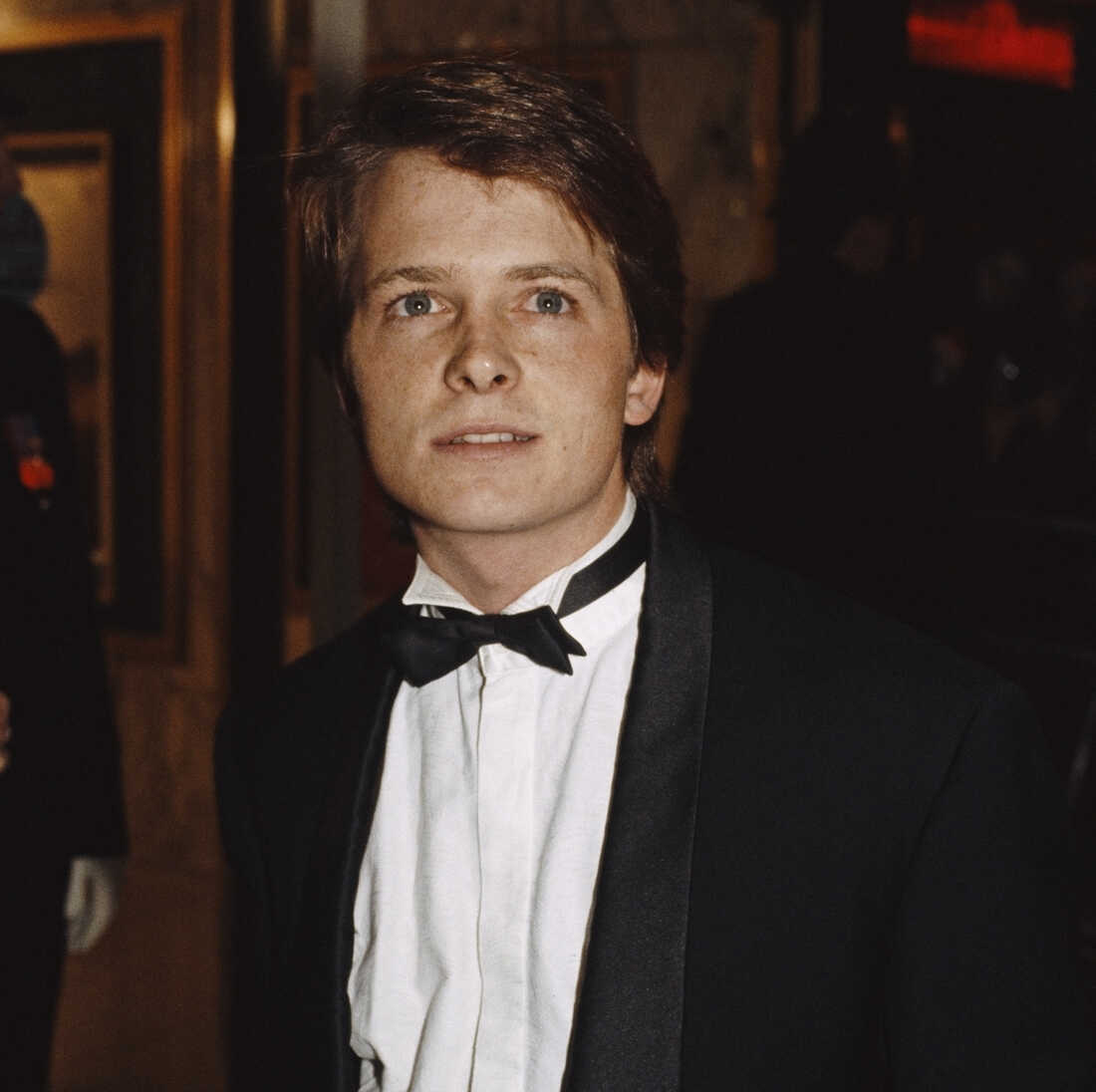

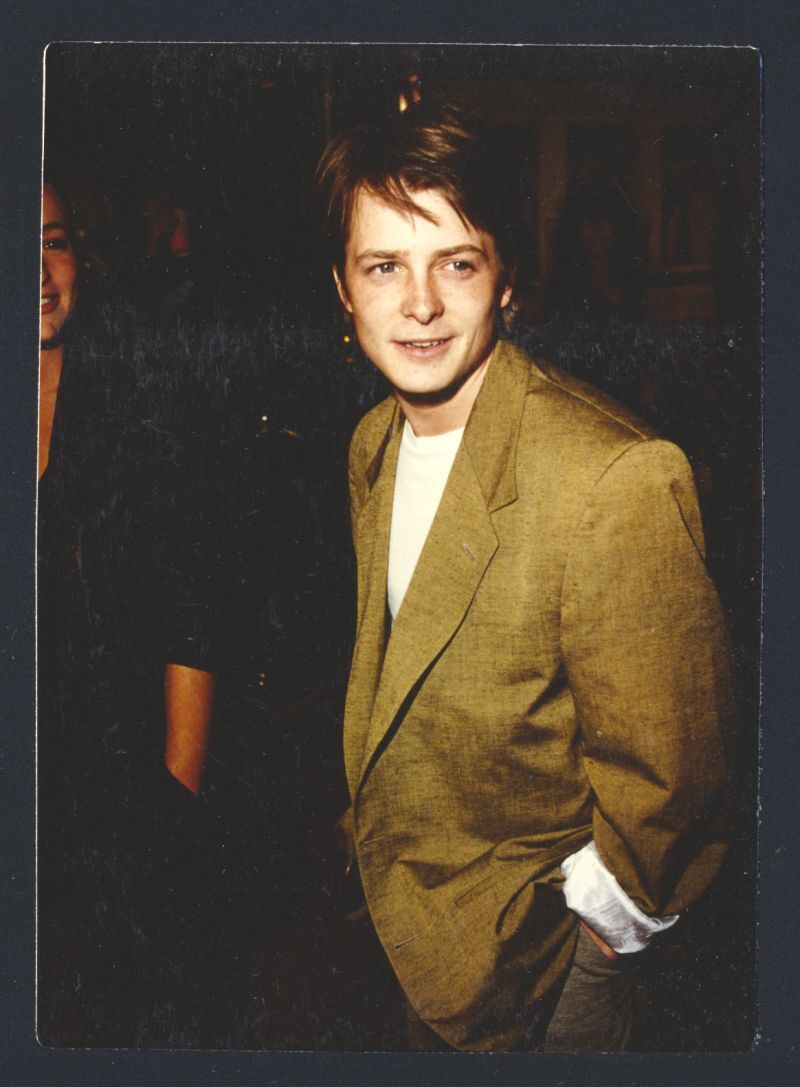

She hesitated before asking her last question. “Do you ever miss the past? Being that kid on screen with endless energy?”

Michael looked out the window, where the sun was beginning to set, casting long shadows across the room.

“I miss some things. Sure. The dancing, the improv, the adrenaline of a live show. But I don’t miss the noise,” he said. “Back then, everything was fast. Now, I get to slow down and see things I never would’ve noticed.”

Like the birds nesting in the tree just outside. Like the way his wife hums when she cooks. Like how his children look at him—not with pity, but with pride.

“I’ve had a big life,” he added. “Bigger than I deserved, maybe. But I’m not done writing it yet. Even if the pages are harder to turn.”

Dana smiled, eyes glassy.

As she stepped outside, Michael stayed in the doorway a moment longer, watching the sky. The door behind him creaked, and for a second, it sounded like Parkinson’s again—knocking.

He looked back and whispered, “Not today.”

Then he closed the door.

And the house fell back into its gentle rhythm—the ticking clock, the distant hum, and the heartbeat of a man who had learned to live without needing to win.

Just needing to be.