Mary Ann Webster was not a woman who sought the spotlight.

Born on a bitterly cold December morning in 1874, in the soot-stained borough of Plaistow, East London, she was the sixth child of a dockworker and a seamstress. From an early age, she understood that life was not always kind, and that kindness itself was often a choice, not a luxury.

She made that choice every day.

By the time she was 19, Mary Ann had qualified as a nurse—a rare feat for a working-class woman in that era. She was tall, broad-shouldered, and calm in the face of chaos. Mothers in the ward said she had a “quieting touch,” and doctors came to rely on her more than they would admit.

In 1902, she married Thomas Bevan, a man with quick wit and kind eyes. He was a florist by trade, known in the local market for making modest bouquets look like royal arrangements. He made her laugh—really laugh—and that was enough. Together, they had four children, whom they raised in a tiny, bustling house with a coal stove, books stacked in every corner, and always, a vase of fresh flowers on the table.

Life, for a while, was good.

But time has its own intentions.

A few years into her thirties, Mary Ann began to notice changes in her body. Her hands ached. Her jaw grew wider. Her once-bright eyes became more deeply set, and her skin thickened. What began as small changes soon became impossible to ignore.

At first, she kept it from Thomas. He had been coughing more lately, his breath shorter than it used to be. Her own worry could wait.

But Thomas passed away suddenly, in the autumn of 1914, leaving Mary Ann a widow with four children and a body that was becoming unrecognizable.

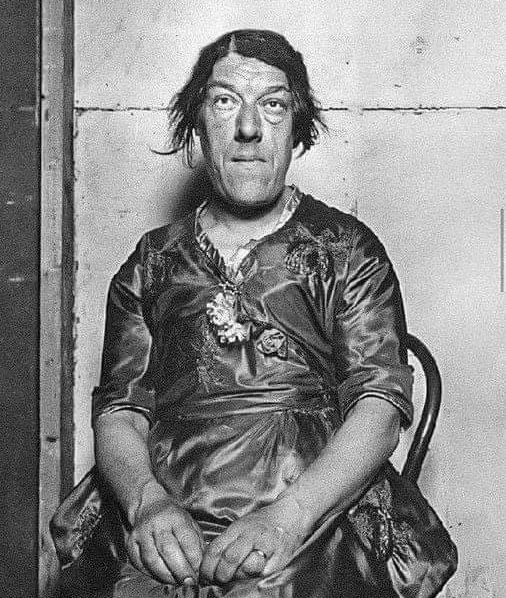

Doctors eventually diagnosed her with acromegaly, a rare hormonal disorder that caused abnormal growth of the bones in her face and limbs. There was no cure, and little understanding of the disease at the time. As her features became increasingly distorted, so did her prospects.

Her nursing job was taken from her—quietly, out of “concern for the patients.” Neighbors began to whisper. Children stared.

And still, she pressed on.

She tried to find work, but doors closed faster than she could knock. Employers couldn’t see past her appearance. Her hands were too large for fine work, her face no longer “appropriate” for public roles. Her savings dwindled. Her children needed food, schooling, shoes.

And so, Mary Ann made a decision that would haunt and empower her for the rest of her life.

She answered an ad in a newspaper looking for “The Ugliest Woman” for a traveling exhibition. The pay was more than she could earn in a year as a nurse.

With trembling hands, she sent a letter.

The first time she stepped onto a stage in a sideshow tent, the lights blinded her. Laughter echoed before she had even said a word.

She had been renamed—“The Ugliest Woman in the World.”

Her heart broke.

But when she closed her eyes, she saw her children. Warm. Safe. Fed. And so she smiled, exaggerated her expressions, and played the role. Night after night.

She toured across Britain and eventually traveled to America, performing at fairs and vaudeville shows, enduring whispers and ridicule from audiences who never wondered about the woman behind the face.

But behind the curtain, Mary Ann was still a mother. She sent letters home every week, tucked with money and small gifts. She made sure her children had books, tutors, and a garden where they could grow their father’s favorite flowers.

And when interviewers asked her why she did it, she always replied with the same words:

“Because no mother would do less.”

Over time, something shifted. The crowds still came, but some began to look longer—not with pity or revulsion, but with curiosity. Then with awe.

Who was this woman who carried herself with such grace? Whose voice held steady, whose eyes held stories deeper than the stage could contain?

She began to speak after performances—short talks about illness, motherhood, and resilience. Some audiences listened. A few even applauded.

And slowly, her story reached beyond the circus tent.

In 1923, a journalist wrote a profile titled “Beauty in Courage: The Life Behind the Mask.” It sparked letters, donations, and a reexamination of how society treated those who looked different.

But Mary Ann never returned to the spotlight to bask in admiration. She returned home.

Her children, now grown, welcomed her at the train station with arms wide and hearts full. She wept—not for her years lost, but for knowing they had been well spent.

Mary Ann Bevan passed away in 1933, in the quiet of her own bed, surrounded by the very love she had fought to protect. The newspapers, for once, chose their words carefully. “Beloved Mother. Fierce Protector. A Woman of Strength.”

They finally got it right.

Her story lives on—not in her condition, but in her choices.

In a world that often valued beauty more than bravery, Mary Ann chose both: to be beautiful in the way that mattered most.

Through sacrifice. Through love.

Through the kind of strength that never needed applause.